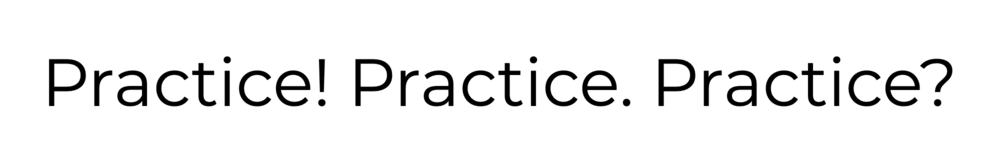

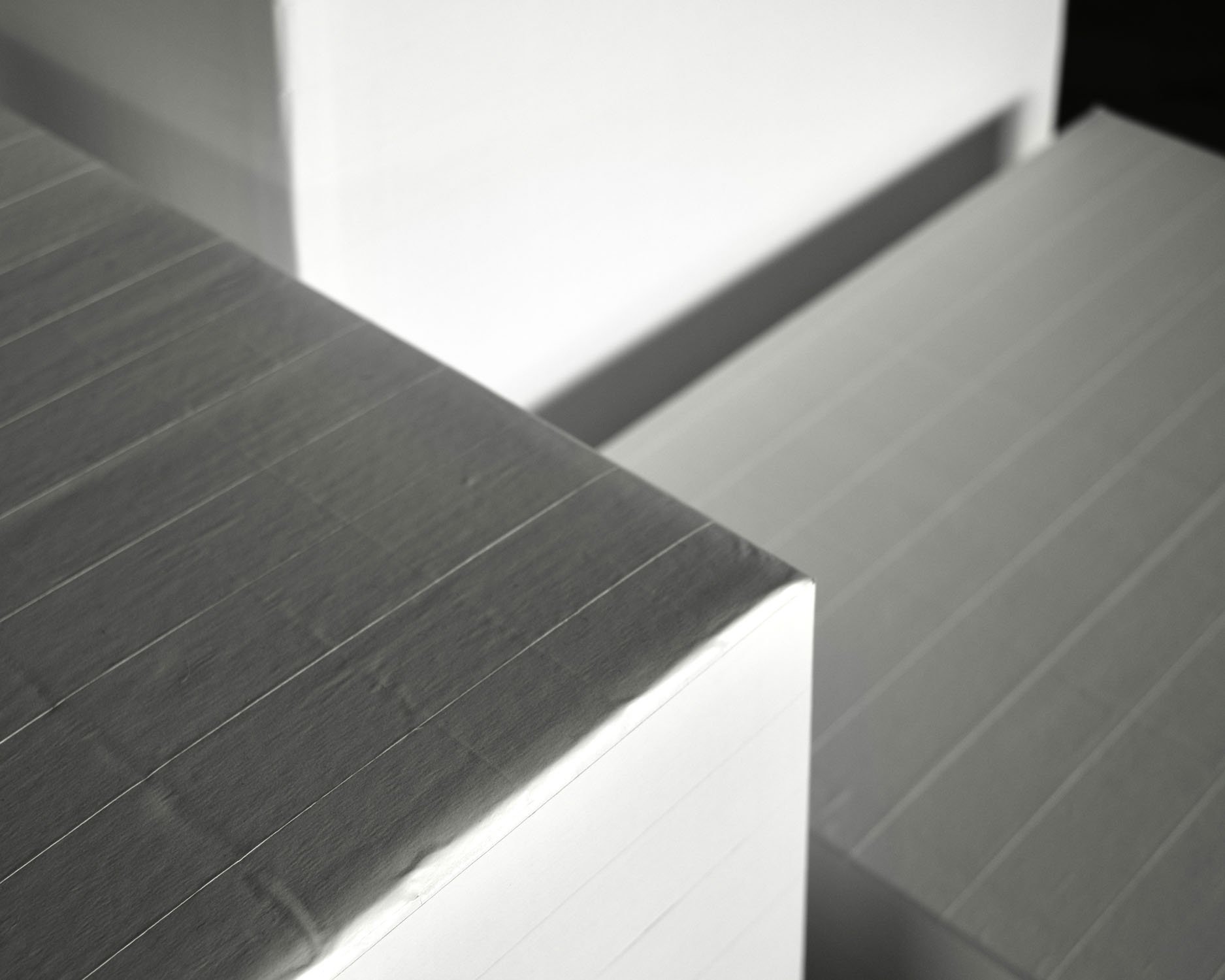

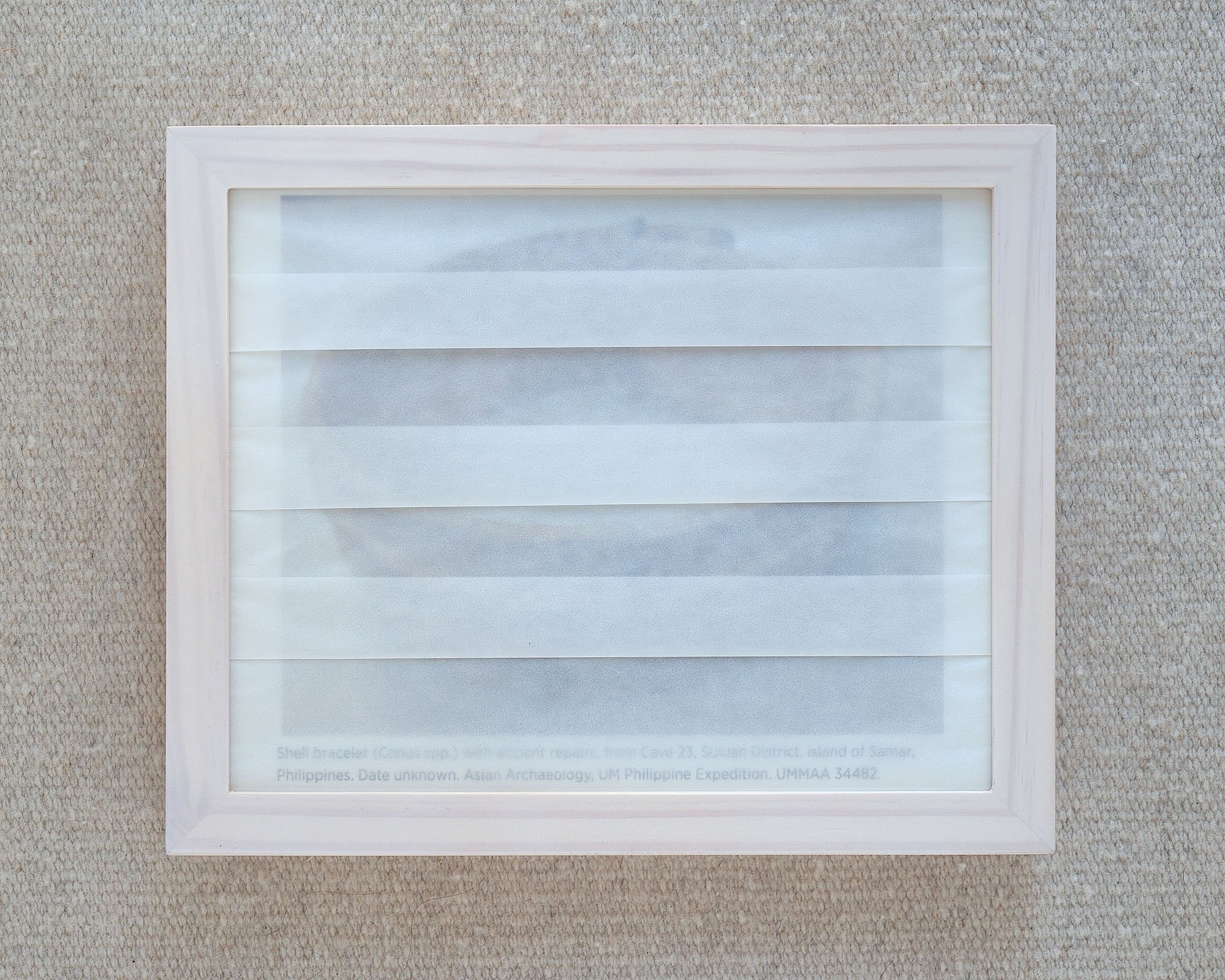

Studio photos of Balikbayan project

A few pictures of the completed works before sending them off to the exhibition!

Balikbayan (Studies for Plinths), 2021

Balikbayan (Studies for Wrapped Gifts), 2021

Site Update: Studies for Balikbayan Box Plinths and Wrapped Gifts

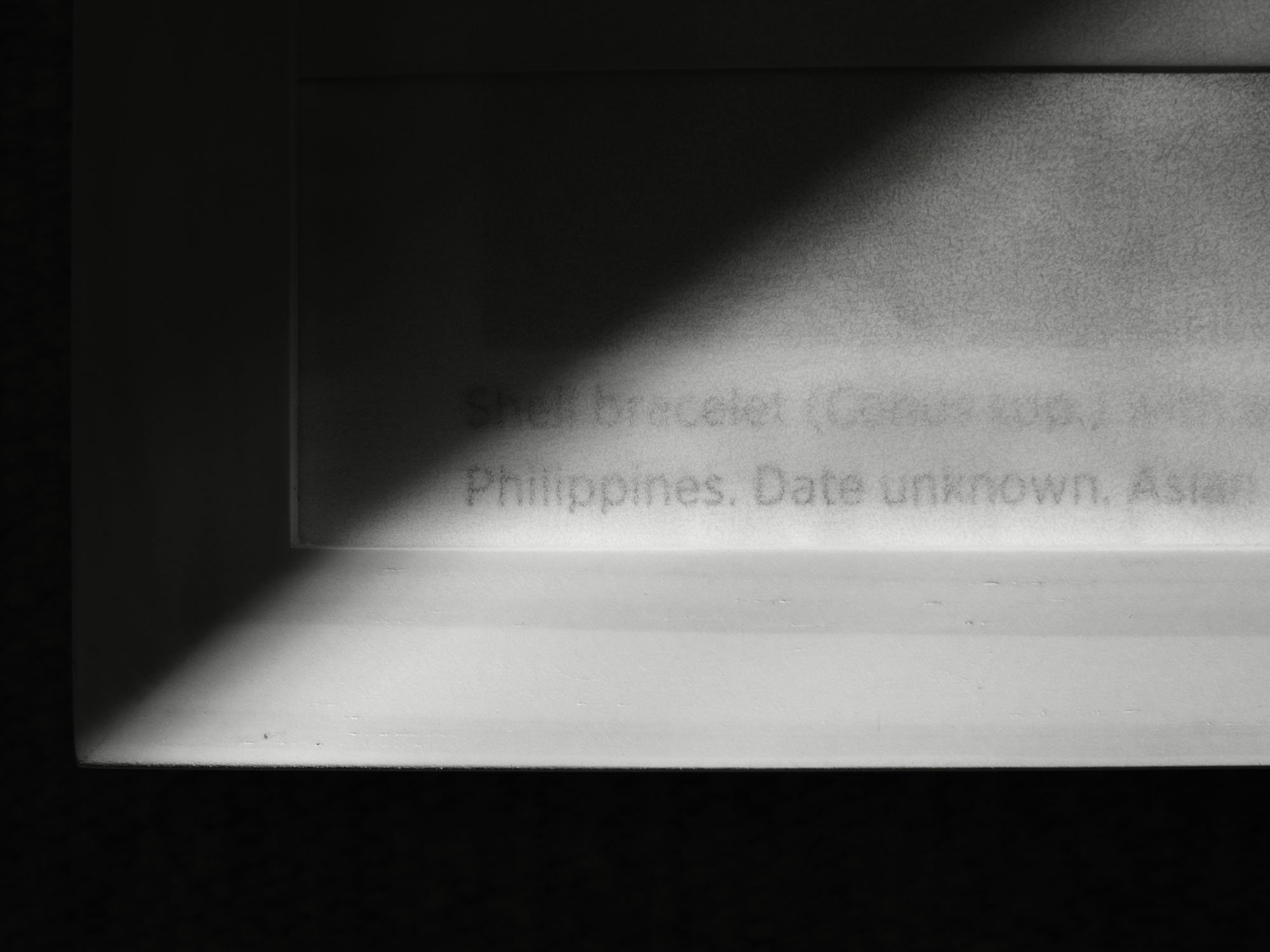

Today I’m opening up my previously private project page (a PPPP of course) for my works involving balikbayan boxes and the imagined extralegal restitution of cultural objects extracted from the Philippine islands by American colonial expeditions. A first iteration of the work is now on view at The Contemporary Austin as part of a group survey, Crit Group Reunion.

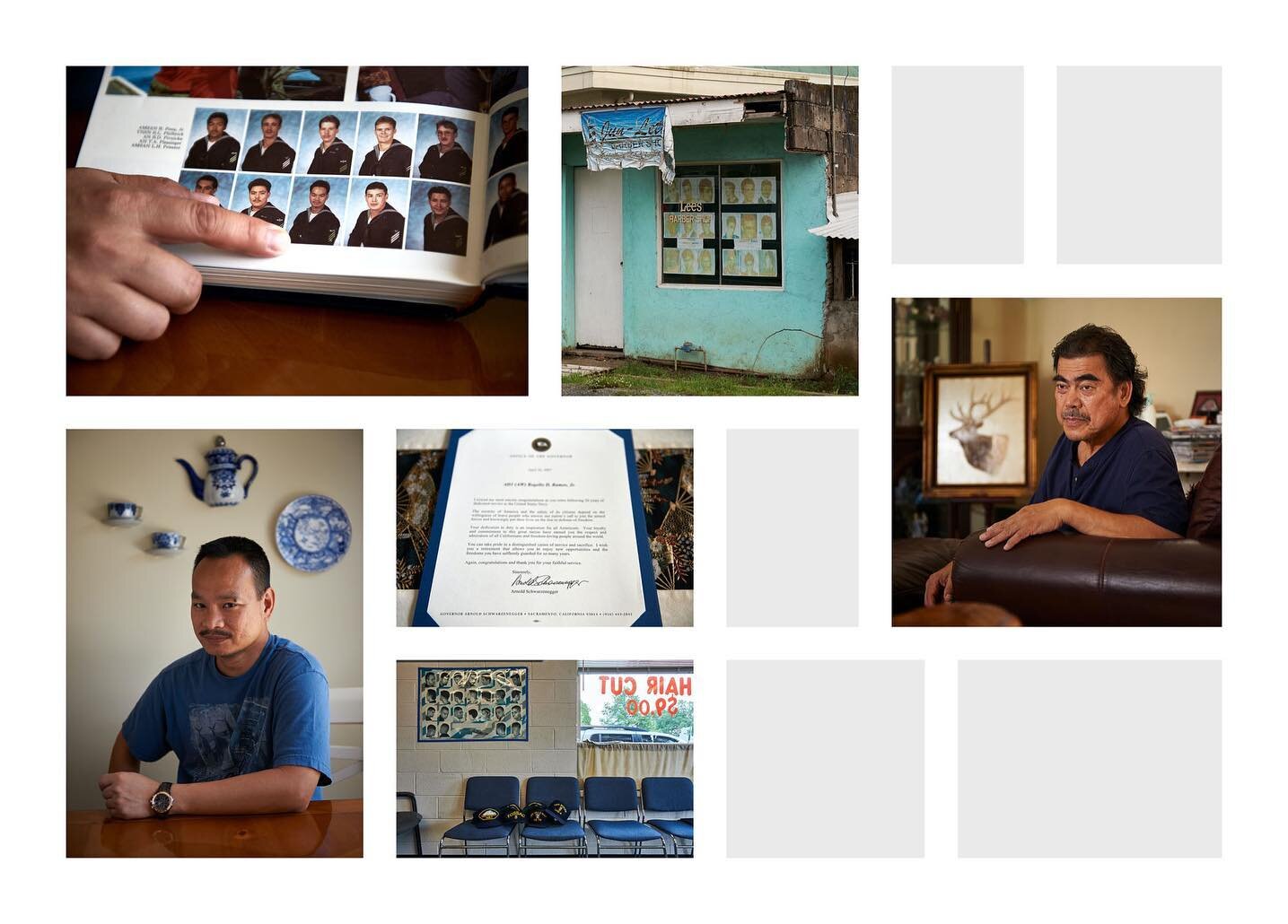

Zoom Artist talk for "Filipino American Navy"

October is Filipino American history month. I’m excited, and truth be told, nervous, to give an artist talk about images from my long-dormant “Filipino American Navy” Project. The talk will mark a kick off of sorts for a physical exhibition of prints that will run at the City of Austin’s Asian American Cultural Resource Center @aarcatx till the end of the year.

I’d like to use the talk to present my own background growing up in and among FilAm Navy families, as well as touch on ideas of labor and identity, immigration and belonging, material culture and the possibilities of photographic dignity.

"What Can Museums and Art Orgs Do to Counter Anti-Asian Hate?"

“The group also thinks that museums should reexamine their own institutional practices, and “ask how their role as exhibition-makers, public programmers, educators, and stakeholders within their respective communities might be doing harm to their Asian and Asian diasporic audiences.”

“Art is indeed a conduit for understanding global culture, but can institutions — especially those that collect and display art and artifacts from Asia and the diaspora — extend their care to the people who have created such works and who labor under their roofs?” the group asked.”

Two articles addressing the historical complexities and psychological compromises of Asian American life in the United States

“Being Asian American has always been a bewildering and complicated experience. You move to a new country and think you’ll be treated like an American, but what you really want is to be treated like you’re white, which isn’t possible.

There is a common Chinese saying of 吃苦 (chīkǔ). It translates literally to “eat bitterness,” to swallow our pain and suffering and endure it. We persevere and we don’t complain, and it is seen as a virtue: Work hard for things that people can’t take away from you. In a study of ethnically diverse cancer patients, they found that Asian Americans reported the lowest pain scores. My mom would not have seen the terrifying incident with our old neighbor as something to tell us about. Sharing it would have meant she was complaining. He used words. He didn’t cause her physical harm. He didn’t even use a racial slur. So, maybe it really wasn’t that bad.

...

The damaging model-minority myth suggests that Asians actually have it pretty good in this country, especially compared to everyone else, and propels a perception of universal success (in reality, Asians have the largest income gap with one of the highest poverty rates). It also implies that with higher education and hard work, you can chīkǔ racism. I’ve been shamefully ambiguous as to how prejudiced white America is to Asian Americans, giving white supremacy the “benefit of the doubt” it did not deserve. I’ve been constantly made to feel like I should be grateful for what I have, but what I really have is an uneasy, panicky feeling that I should have spoken up for more and sooner.”

via The Cut

“And here we come to the heart of the complexity of “speaking up” for Asian-Americans. Thanks to the “Model Minority” myth — popularized in 1966 by the sociologist William Petersen and later used as a direct counterpoint to the “welfare queen” stereotype applied to Black Americans — Asian-Americans have long been used by mainstream white culture to shame and drive a wedge against other minority groups.

...

These past few weeks, it seems as if Americans have opened to a kind of knowing. As I saw these recent incidents of anti-Asian violence unfold in the news, I felt a profound sense of grief. But I also experienced something akin to relief. Maybe, I thought, now people will start to respond to anti-Asian violence with the same urgency they apply to other kinds of racism.

But then I started to feel a familiar queasiness in the pit of my stomach. Is this indeed what it takes? A political imagination (or, really, lack thereof) that predicates recognition on the price of visible harm?”

"Walis tambo" and the Capitol Insurrection

“While Asian-American voters delivered for Biden in battleground states, one in three Asian-Americans across the country supported Trump, an analysis by the New York Times showed. ”

“While others laughed, the broom man was generally slammed on social media in the Philippines, as people expressed disgust at the support for Trump and the mob.”

Interview with photographer Ryan Frigilana

Filipino American Artist and Art Community Manifesto

““During the past month, we’ve been working on a collaborative writing exercise to develop a collective manifesto for the directory. We hope that this piece will help to uplift and give you strength and power to move forward as it has for us.

Maraming salamat to all the artists who contributed to this writing, named and anonymous “”

Possible directions, possible concerns for FilAm Navy Project

Is Filipino American Navy a personal project in public relations? If not, why not? If yes, so what?

Within this project, I operate in parallel tracks of identity and mixed feelings in an attempt to draw out the ways in which photographic images have shaped, and may continue to shape, Filipino American claims to participation, presence, and dignity in the United States.

As a son and brother to two people who served in the U.S. Navy, I’m interested in exploring how the conventions and expectations of formal photographic portraiture frame ideas of dignity and status. I’d like to discover to what extent associations with military service in particular provide significant, additional, and legitimizing claims to national belonging. Does a picture of my father or brother in uniform make them more understandable and readable as Americans?

As a naturalized citizen who was born on a U.S. military base in the Philippines—one that no longer exists—I’m interested in how Filipino American military families share and display the possessions of their documented past, both the formal and casual photography as well as the paperwork and memorabilia, to reflect and tell their stories within private, domestic spaces. I wonder in what ways these documents and objects and arrangements drift away from embodiments of personal and familial pride, and towards mere evidence in the eyes of visitors like myself. Does the intervention of my photography reflect ideas of pride and agency and self-determination, or am I only using the content of these pictures as bulwarks against discrimination and prejudice from potential audiences?

As a thirty-eight year old Filipino American arguably in the middle of my working life, I’m interested in experiencing how invitations to make pictures of domestic spaces, largely by retired career military families, furnishes specific ideas about accumulated material and financial success. I wonder to what extent these invitations might lead to further conversations about personal aspirations, dreams and ideas of home and security, and idiosyncratic and generational visions of America.

As a visual artist working within the traditions, technologies, and discourses of documentary photography, I’m interested in asking—and worried about the answer to—two questions. First, if I can make it visible, will that make it legible? And second, if what I’ve made is legible, who am I asking to do the work of looking, reflecting, and understanding?

I would like to compare and contrast these four tracks of identity and indecision with the making and recording of portraits and domestic encounters with Filipino Americans, their objects and manners of display. Further, I would like consider these efforts with and against larger historical and institutional modes of preservation and presentation, especially as they relate to postcolonial understandings of the imperial museum and archives, two linked structures that continually signify the simultaneous accumulation and dispossession of indigenous Filipino artifacts and materials in the United States.

In the photographic process of taking, making, accumulating, and sorting, will I find strategies and contexts and genuine ways to resist—or will I inadvertently reinforce—the very processes of knowledge production and display that have historically reduced Filipino Americans, and Asian American generally, to an observable type?